You’d think that having Baby Boomers as parents—the original “Me” generation, the hippies, the counter-culturists—would mean my parents would be mellow, go-with-the-flow types. Nope. Something happened when they boxed up their bell bottoms and platform shoes, and traded their peace sign for a wagging, “you’re-in-trouble” finger.

I’m a Millennial who grew up in a strict household with restrictively high standards. If I got a B in my report card or strayed from my size 5 hourglass figure, I was punished. This lead to the development of my own complexes, smudging any sense of accomplishment I may feel with my stubby, perfectionistic fingers.

Watching my nephew grow up is witnessing a life lesson in action. Babies are born with the insight that everything they do and everything about them is wondrous. Sticking your foot in your mouth is an accomplishment, not cringe-worthy. When I told my nephew not to throw his food on my perfectly spotless floor, he looked me straight in the eye, grabbed his perfectly diced sweet potato, and proceeded to drop it on the floor.

“Say it’s wrong,” his look seemed to say. “Because I think it’s totally awesome to make a mess.”

At some point, something does go wrong with many of us. We learn to associate success with perfection and failure with imperfection. If we don’t fit into what is considered the ideal, we believe we are flawed, and in extreme cases, broken beyond repair.

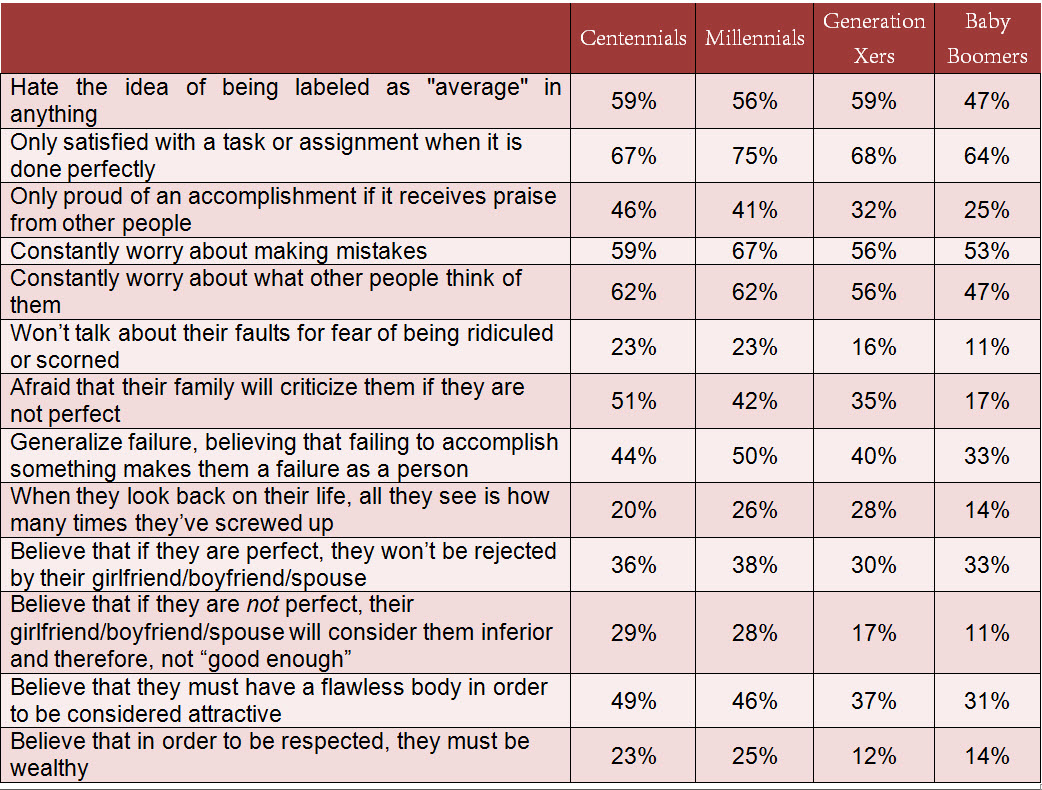

When I analyzed data from 1,324 people who took our Perfectionism Test, I divided the sample into generations. Here’s how they break down:

(Note: Generation birth ranges vary depending on the information source. This is because there is no universally agreed-upon definition for generations. Instead, these ranges are determined by researchers, sociologists, and marketers who often use different criteria. In this study, I used birth ranges defined by The Center for Generational Kinetics, otherwise known as GenHQ).

- Generation Z, aka iGen, aka Centenntials. Born between 1996 and 2012.

- Generation Y, aka Millennials. Born between 1977 and 1995.

- Generation X. Born between 1965 to 1976.

- Baby Boomers. Born between 1945 and 1964.

I then assessed the degree to which each generation feels pressured—from family, employers, society, or themselves—to be perfect. Here’s what the data revealed:

It seems that Centennials and Millennials have developed the belief that love, respect, and acceptance are contingent upon how close they are to perfection in every way. In my opinion, this pressure to be perfect, although often self-imposed, could originate from pressure from parents, teachers, friends, or the media. How many times in a day are we inundated with the message that we are hopelessly flawed if we don’t look, smell, or dress in a specific way, get good grades, get into a good school, make a lot of money, get married, buy a certain type of car, etc.? Many times.

Young people who feel that they not good enough or not close enough to their concept of “perfect” believe that they are flawed. Once this belief is internalized, it results in self-esteem issues, self-image problems, the tendency to set impossible standards, and harsh self-criticism when these standards are not met. This in turn could lead to mental health issues or compel a person to adopt extreme measures to reach these impossible standards—like starving themselves in order to achieve a “perfect” body.

If that doesn’t scare you enough, research has also shown that in some cases, extreme perfectionism can lead to self-harm and increase suicide risk (Chester, Merwin, & DeWall, 2015; Claes, Soenens, Vansteenkiste, & Vandereycken, 2012; Flett, Hewitt, & Heisel, 2014). Think about that for a moment. Some people are intentionally hurting themselves, even fatally, to relieve the pressure of trying—and failing—to be perfect.

Fellow perfectionists, let me make this as clear as possible: Perfectionism is not a strength. It’s not something to be proud of. Most importantly, it’s a pursuit that will never, ever, be achieved. By all means, do your absolute best in everything you take on, but know that your best is more than good enough. And mistakes are awesome.

They’re like road signs that tell you whether you’re going in the right direction or need to change course, maybe even ask for directions. Moreover, you don’t have to live up to anyone’s expectations of who you should be or what you should look like.

You are not broken. You are the perfect version of a wonderful, vulnerable, emotional human being.

Insightfully yours,

Queen D

References

Chester, D. S., Merwin, L. M., & DeWall, C. N. (2015). Maladaptive perfectionism’s link to aggression and self-harm: Emotion regulation as a mechanism. Aggressive Behavior, 41(5), 443–454.

Claes, L., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Vandereycken, W. (2012). The scars of the inner critic: perfectionism and nonsuicidal self-injury in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(3), 196-202.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Heisel, M. J. (2014). The Destructiveness of Perfectionism Revisited: Implications for the Assessment of Suicide Risk and the Prevention of Suicide. Review of General Psychology, 18(3), 156-172.