After achieving my Psychology degree, I wanted to broaden my intellectual horizons by taking some courses that would allow me to put my theoretical knowledge into practice. Management, it seemed, was a good place to start. Why? Because I had worked under a lot of take-charge managers who knew nothing about how to handle the people side of management. I started with a course at a business school that was affiliated with my Alma mater, and in the very first class, the professor asked the following question:

“Why do you want to become a manager?”

He strolled around the class, choosing people at random to answer the question. There were a lot of “I want to bring out the best in others,” and “I want to move up in my career”. And then the teacher asked the girl sitting in front me:

“I like telling people what to do. I like being in charge and bossing people around.”

I, along with the rest of the class, thought she was joking. She wasn’t. She didn’t blink an eye. She didn’t laugh or smirk. There was absolute silence in the class for a few seconds until the teacher, clearly thrown off by her bluntness, jumped into the lecture. But her answer shook me. It hung in the room like a specter. When the teacher announced a break an hour later, I picked up my bag and left. I never returned.

I’ve never been interested in positions of power. I have found myself unknowingly taking charge of a situation during a crisis, but I don’t need to be in a position of authority to be content. Besides, as a “follower,” I’m in a prime position to observe people who do take charge, and there is one thing I’ve come to learn: Power only corrupts the corrupted. But not all people who are driven to gain power do so for selfish reasons.

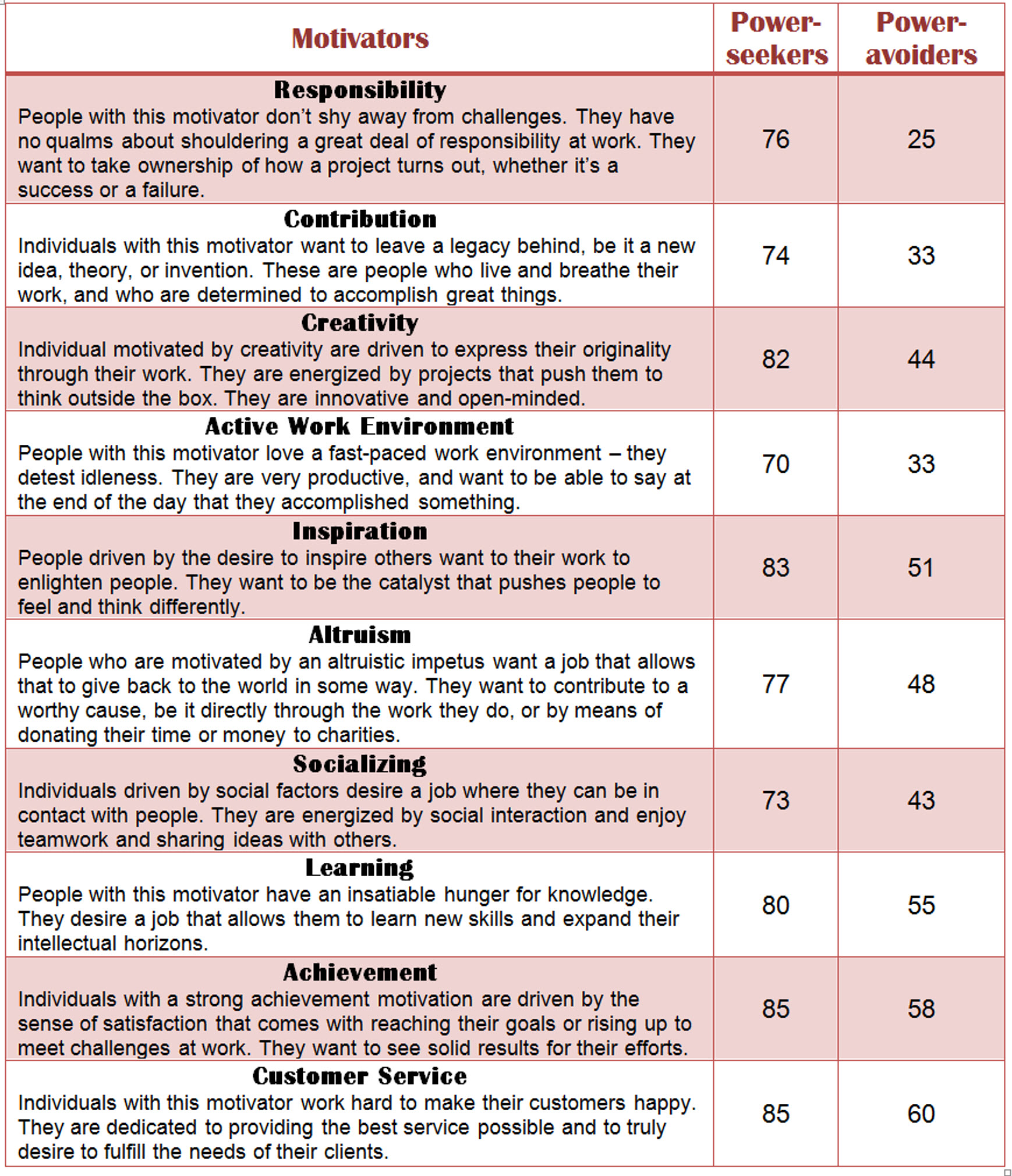

I recently analyzed the profiles of 738 people who took our Career Motivation Test. I split the participants in the study into two groups: Those who are highly motivated to be in a position of power at work and those who are not. What I discovered, much to my pleasant surprise, is that power-seekers are driven by many other motivators, including the following:

(Note: Scores range on a scale from 0 to 100; the higher the score, the stronger the motivator).

Essentially, what these stats reveal is that the pursuit for power is not necessarily driven by a sense of superiority, selfishness, narcissism, or may favorite word du jour, Machiavellianism. I think a lot of people want to move up the ranks because they believe that they will better serve not just themselves, but everyone. More power means more freedom to make a difference, to initiate change, and to do what every good leader should do.

In our study, people who are determined to work hard in order to achieve a position of power also want to accomplish many others things. They want to express their creativity, inspire people, and give back to the world. This totally flies in the face of many of our beliefs about what drives someone to desire power. But here’s what we need to keep in mind: It’s the motivation behind the desire for power that matters. It’s why some leaders can use their influence effectively and not let power get to their head – people like Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Insightfully yours,

Queen D